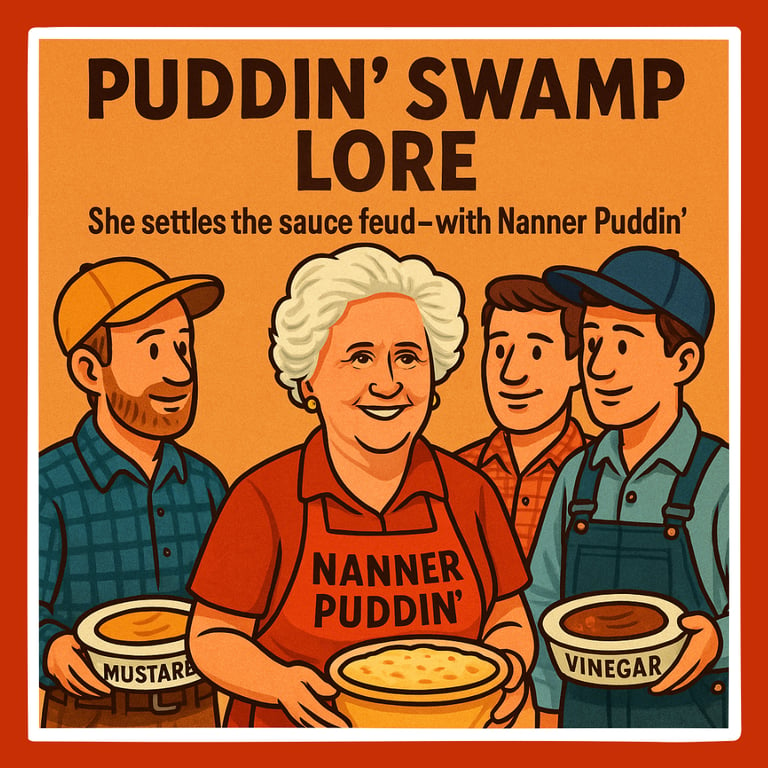

BarBQ in the Puddin’ Swamp: A Turbeville Porch Tale

Step onto Opa’s porch for a Turbeville tale of barbecue, brothers, and Mother Martha’s hush-puppy gavel that kept peace in the Puddin’ Swamp.

PEOPLE & PORCH STORIESFOOD, FIRE & FRONT PORCHES

Rom Webster

Barbecue, Brothers, and Nanner Puddin’ in the Puddin’ Swamp

Here’s a front-porch tale from the Puddin’ Swamp country—a place where the cypress leans like it’s listening for gossip, and every family owns a sauce recipe and an opinion strong enough to bend nails. Yes, the Puddin’ Swamp is a real place. Let me tell you about it.

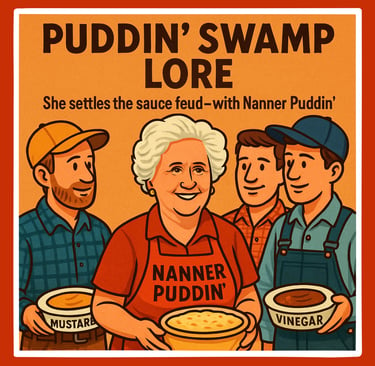

They’ll tell you in Turbeville that a person’s barbecue loyalties are born with their first tooth. Sam Turbeville (no relation to the town founders, though he liked to hint otherwise) swore by mustard—bold, gold, and bossy. Sam’s middle brother, Russell, kept a crimson jug of tomato sauce by his bed like a prayer book. Russ liked sweet things. And then there’s the youngest brother David. He couldn’t have been much different from Russ, and nowhere was that more evident than BarBQ sauces. David believed vinegar was the only honest preacher in the church of BarBQ—thin, sharp, and sanctifying.

They’d argue at reunions, at the gas pump, and even standing hip-deep in the garden shelling butterbeans. It wasn’t mean—no, sir. It was the cheeriest feud you ever heard. But it did get… persistent.

One July, the brothers made a scoreboard on a piece of plywood: SAM 7, RUSS 6, DAVE 5, and—down at the bottom—MOTHER MARTHA: 100. That’s because Mother Martha—their mama—never lost an argument or a baking contest either. Elegant as a Sunday hat and plainspoken as a county map, Mother Martha was famous for two things: the warmest hospitality in Clarendon County and a banana pudding so silky it could make a deacon forget his diet and a deer hunter lay down his rifles to pick up a spoon.

Folks called her “Mother Martha” because that’s what she was to everybody who came through her kitchen—family, neighbor, lost traveler, even that one game warden who swore he only “happened” by at suppertime. Whenever the brothers’ debate got really hot, she’d set down a platter of hush puppies with a look that said, “I’m the judge. Here’s my gavel. Court is in session.” And somehow the room would get quiet enough to hear cicadas on the other side of the swamp.

And that brings us to a basic, Palmetto State truth: “pile a plate high enough with hush puppies, and even the noisiest sauce sermon quiets without an amen.”

Somewhere near Turbeville lies the wet whisper of Puddin’ Swamp, a lacework of creeks and boggy runs that drift toward the Black River. Old-timers say that pioneer families settled the high ground there and learned to react to the swamp’s moods—flood one year, fish the next. There’s even a campfire theory that the swamp’s name actually started as “Buddin’,” after the bud-swollen cypress in spring, at least until a clerk with a dull pencil wrote it “Puddin’.” Nobody bothered to fix it because it actually sounded friendlier. Another tale says that a traveling preacher once proclaimed that the land there “flowed like pudding after a good rain”—which is the kind of preaching that’ll get you invited back for dinner and dessert too.

Whether by pencil or preacher, “Puddin’ Swamp” stuck like molasses, and the people around there made a habit of celebrating together—most loudly each April when the Puddin’ Swamp Festival rolls down Main Street with bands, parades, and more pulled pork than a football tailgate at Willy B Stadium. This particular story, the one you’re about to hear, lands on the Friday of festival week a few years back. In those days, Sam ran a mustard-yellow stand shaped like a seed shed. Russell cooked under a tin awning painted cherry red. And David, he smoked shoulders beside a whitewashed pit that he called “Revival.”

Someone—no one ever proved who—entered all three brothers in the Puddin’ Swamp Cook-Off that year. The prize was a blue ribbon, a silver ladle, and bragging rights stout enough to season a Thanksgiving dinner. The flyer listed for that year’s particular the judges: the school principal, the postmistress, and, for local color, a retired fishing guide who claimed to know every bend of the Black River by the smell of the water alone. Mother Martha was not on the panel. “That’s for the best,” she said, patting her pearls. “I’m partial to peace.”

The brothers cooked through the afternoon, mopping, watching smoke, shooing gnats with palmetto leaves like altar boys in July. The crowd grew and so did the good-natured heckling. “Sam! That mustard’ll strip paint!” “Russ, your sauce has more sugar than Vacation Bible School.” “Dave, your vinegar reminds me of my science experiment in middle school!”

Just before judging, a thunderstorm bigger than a Texas tornado rolled over the swamp and rattled its windows. The first melting fat dripped on the hot hickory and turned the swamp air into sweet perfume from heaven. Meanwhile, the power flickered. The band unplugged. The judges huddled under a tent flap. And the cook-off director—a nervous fellow in a visor—realized he had left the fancy gavel they’d planned to use for the awards back at the town hall.

“You can use this,” Mother Martha said, stepping forward with a brown paper bag. She reached in and produced a giant hush puppy the size of a baby’s fist—crackly outside, soft inside, steam curling like a ribbon. “A judge’s gavel needs to be heard,” she said. “And it should also be eaten when the verdict’s done. Nobody ever argued with a mouth full.”

Sam grinned. Russell tipped his cap. David whispered, “Amen.”

The judges took their plates. Sam’s mustard kissed the pork like sunshine—bright, punchy, confident. Russell’s tomato sauce hugged the meat in sweet-savory red, like a church potluck in July. David’s vinegar cut through with clean edges and pepper, making the smoke sing higher. The principal declared it a three-way tie for “Best in Its Own Right,” which is the sort of decision that keeps a principal from getting cornered in the grocery store.

But the fishing guide—skin like tanned leather, eyes river-blue—cleared his throat and pointed a fork toward the crowd. “Listen,” he said, and everyone did. The rain had gentled. Out past the booths you could hear Puddin’ Swamp murmuring—water shouldering through reeds, frogs calling each other, a barred owl scolding the weather. “That swamp’s taught me two things,” he went on. “One, everything flows into something larger than itself. Two, balance keeps you afloat. Mustard, tomato, vinegar—each one’s a current. On a good plate, they meet.”

The postmistress nodded. “Like letters, packages, and money orders—different, but it’s all the same window.”

The principal lifted the hush-puppy gavel and brought it down lightly on the table. “Then here’s our ruling,” she said. “The Blue Ribbon for Sauce goes to… Mother Martha, for the only recipe that never caused a fight.” The crowd laughed and clapped. “And the Silver Ladle for Barbecue goes to the Turbeville brothers, jointly, for proving that three roads can lead to the same table.”

“Objection!” shouted a boy from the 4-H tent, mostly because he wanted to see what the gavel tasted like. Mother Martha obliged, breaking the hush puppy in half, then in quarters, handing pieces around until even the mayor had crumbs in his goatee.

That night, the brothers served from one long line, each man saucing the other’s meat as asked. Folks learned you could lay a mustard stripe beside a tomato swoop and still dribble vinegar over both—no lightning bolt required. The scoreboard back home got retired to the barn, and a new sign took its place over the kitchen door: “In this house, we serve three kinds of yes.”

Later, under Mother Martha’s porch fan, the brothers asked her how she made peace taste like dessert.

“Same way the swamp does,” she said, spooning out Nanner Puddin’ to the three of them and a stray cousin who had an instinct for being nearby at spoon time. “Start with something old enough to have roots. Then fold in what’s lively. Never skimp on the sweet. And be patient, boys—stir gentle, and let it set. You can’t rush pudding, and you can’t rush people.”

Sam took a bite and sighed like a hymn at the last verse. Russell leaned back and declared he might just name his first daughter Banana if his wife would allow it. David, whose vinegar had been known to clear sinuses from Marion to Kingstree, dabbed his eyes and blamed it on the pepper.

The next morning, tourists rolled east toward the Grand Strand, and some of them stopped for breakfast biscuits in a town they’d never heard of. They asked why everyone looked so pleased. The clerk grinned and said, “Because the Puddin’ Swamp decided the best sauce is the one you share.”

And that’s the truth of it. Around Turbeville, the debate keeps folks lively, like frogs on a wet evening. But when the hush-puppy gavel falls and the ‘Nanner Puddin’ comes out, even hard opinions soften. You can stand on your flavor and still pull up a chair—especially if Mother Martha is holding the ladle.

Our Story

There are some folks who would tell you that this didn’t happen, and others who would say it did, but not exactly the way OpaDopa told it to Rom (the author of this blog post). But nevertheless, that’s our story and we’re sticking to it!

And we have a special treat for you below. We sat down on the porch with OpaDopa just before we published this article. It happened out there in the Bull Swamp near the banks of the Edisto River. It was right there at the Palmetto Barn—that’s where we persuaded OpaDopa to tell us this same story in his own words.

We recorded it as it happened—no edits! Just the real deal from OpaDopa. And we have it for you below.